- Fashioned

- Posts

- It Shouldn't Be This Hard to Dress for Lunar New Year

It Shouldn't Be This Hard to Dress for Lunar New Year

When 1.5 billion people celebrate, why are there so few brands that make high quality cheongsams and other LNY attire?

It’s a couple of days into Chinese-slash-Lunar New Year as I’m writing this, aka the most consequential holiday on the Asian calendar, but the year of the snake started out a quiet one for me. My family lives in Australia and I did a brutal 22 hour flight and time-zone flip from Sydney back to New York in early January so I wasn’t about to repeat that so soon. The holiday also had the decency to start a few days before New York Fashion Week rather than arrive right on its tail-end as it did last year.

These days, I give out more laisee or red packets than I receive (hello, getting older!) but I swear that’s not the main reason for being less out and about lately. It’s a relief because every year I get stuck with the same dilemma: Where can I find a stylish, quality cheongsam or otherwise LNY-appropriate outfit to wear?

Well-designed off-the-rack retail options are thin. The choices fall mainly to one of two camps: choose a cheaply-made version or spend a chunk of money (anywhere between $400 to $1,000+) and a not insignificant amount of time to tailor one—if you’re lucky enough to be in Asia and in proximity to a skilled tailor, that is. I have more often than I’d like to admit just thrown on a few items of red clothing and called it a day.

Which is so odd when you consider that the holiday is celebrated in so many countries: China, South Korea, Vietnam, Singapore, Malaysia, Philippines, and Indonesia. Some quick DeepSeek math tells me that’s about 1.5 billion people who are out there spending—in many cases just outright handing out cash to their friends and family—and it’s specifically a time meant for buying new clothes.

I’m not alone. “I actually have never worn a cheongsam ever, not even for my wedding,” said the fashion stylist and editor Diana Tsui, who is Chinese-American. “Just because growing up in the US you kind of have to actively embrace that part of your culture.”

She’d just been at the Lunar New Year Dinner hosted by the designer Phillip Lim, where guest outfits ranged broadly but few if any wore something resembling a cheongsam. “Phillip went traditional but other people just went for festive fun wear,” said Tsui. “[Model] Mona Matsuoka was in a see-through catsuit and I was wearing a Simone Rocha dress so it kind of really runs the gamut. I think everyone just wants to be fashion-y and cool and sort of festive without being too on the nose.”

The cliched gold standard for the cheongsam (also called a qipao if you’re a Mandarin-speaker) is Maggie Cheung in Wong Kar Wai’s In The Mood For Love. There are countless odes to the costuming in this film. See this discussion, here, and here for an initiation. But it’s cliched for good reason, the outfits are one-of-a-kind.

Maggie Cheung’s cheongsams stole the scene in the film In The Mood For Love.

Years ago, I visited Linva Tailor in Hong Kong, one of several tailor shops who worked on Cheung’s wardrobe. I was fully committed to tailoring my first ever proper cheongsam but I found their fabrics muted and stodgy. None of them had stretch and with that kind of unforgiving silhouette, I left intending to buy some of my own textiles elsewhere and bring it back to them. But life happened and I never got around to it.

The Modern Cheongsam

Over the years to make do, I’ve tried pieces from the high street, like the Singaporean brand, Love Bonito. It’s modernized—so think separates and looser-fitting—but it definitely is better for casual affairs. It’s focused on summer fabrications (because Singapore) and at the end of the day, it’s the Asian equivalent of H&M so it can only get you so far.

There are a handful of designer brands that put their own spin on the cheongsam. There’s Hong Kong’s Vivienne Tam, who in 1994 when many people in mainland China had not quite relinquished their Mao suits, launched her brand with Chinese design details as a core tenet. There’s Shiatzy Chen in Taiwan, who is close with the actress Michelle Yeoh and regularly dresses her but the aesthetic skews to an older customer. I have never been tempted to buy anything from the brand. And yes, there’s Shanghai Tang which sometimes genuinely has nice pieces but is a mess of a business and can’t figure out it’s identity in a post-colonial Hong Kong.

It’s really not for lack of brand attention to the holiday. Everyone ranging from All Birds to Louis Vuitton release an annual Lunar New Year collection. Done well, it looks like Loewe highlighting Chinese traditional crafts of cloissonne, kitemaking, and puppetry, a playful Miu Miu activation at an outdoor ice rink, or Bottega Veneta’s visit to Liu Yang, the birthplace of fireworks. Done lazily, it means turning out a red version of an existing product and slapping on whatever that year’s zodiac animal is.

The bigger fashion brands are very into events and accessories for Lunar New Year and some get really creative with it. They make red packets, mahjong sets, keychains, scarves, you name it—take a second to check out this montage of some pretty charming 2025 knick knacks—however, they don’t attempt to truly design any fashion for the occasion.

Influencer Natalie Lim Suarez, who recently hosted a Lunar New Year dinner with the cheongsam-focused label Sau Lee, said that’s due in part to “accessories [being] a lot easier to sell.”

That much is true. There’s no sizing to worry about but also, the holiday always nudges up against Valentine’s Day so I suspect a lot of brands are trying to produce one generally red-themed collection to hit two birds with one stone.

Suarez’s first cheongsam, she told me, was made by the Malaysian designer Khoon Hooi, who creates beautiful high-end versions with a Peranakan slant. Suarez wishes there were more designers following suit.

“I think Chinese designers should put out more interpretations of the cheongsam because it's an elegant piece that can honestly be worn year-round,” Suarez said. “My girlfriends want to continue wearing their cheongsams to galas, parties, and even weddings throughout the year.”

While Suarez’s own mother is Chinese, the cheongsam is about getting “in a mindset of feeling decadent and feminine,” she said. “I think people from all cultures can embrace the traditional design and wear it in their own way.”

Cheryl Leung, the designer behind Sau Lee, is very much in the camp of normalizing the cheongsam no matter the wearer’s culture too. The Hong Kong brand counts the US as its biggest market and produces designs at an advanced contemporary price-point.

There are a few hurdles, she said. Although vaguely kimono-esque robes have been co-opted by festival-goers the world over and have found a place as an easy mix-and-match item, the mandarin collar and typically body-con nature of the cheongsam is more suited to formal occasion-wear, Leung pointed out. She’s also seen a fear among non-Chinese wearers of being slammed for cultural insensitivity.

Unlike in the 90s and early 00s when a number of celebrities appeared in Chinese-inspired attire on the red carpet, it’s turned into something of a faux pas as the Overton window shifted to viewing it as appropriation. And while Japan and South Korea benefit from a soft culture halo effect, US-China relations have deteriorated steeply.

“We have had a few customers ask every now and then very respectfully, very kindly, ‘is it okay for me to wear this piece?’” Leung shared. “Yes, we want everybody to be able to wear our pieces and feel beautiful. It’s not just for a specific culture…As long as it's done respectfully, I think there shouldn't be a problem.”

The designer Vivienne Tam has made an entire career of internationalizing the cheongsam. Three decades ago, she debuted in New York with her east-meets-west designs, remixing it with denim and even controversial political elements like the Mao portrait. It attracted A-listers like Julia Roberts and Naomi Campbell.

Lately, however, she thinks the rate of westerners wearing the dress has taken a dip. “I think [they wear it] maybe a little bit less than before because of the tension between countries. But also the economy was so good in the 90s,” Tam said. The item isn’t seen as a core wardrobe item, she continued, but a novelty so people may be reluctant to spend on what they see as a less versatile piece.

Tsui, on the flip side, thinks there’s a widening opportunity the past few years for culturally Chinese clothes to shine. While Covid-19 did see a spike in anti-Asian sentiment, it also led to a defiant surge of pride among the Chinese diaspora. She points to wider adoption of the holiday—in 2022, California made it a state-wide holiday and New York and Colorado followed suit in 2023. Tsui has noticed more and more fashion brands are hosting dinners and throwing celebrations too.

“It's also an evolution of a generation of Asian Americans who were born in the US, educated in the US,” she said, “and have risen up into positions of power being like, ‘Hey, this is something we celebrate. You acknowledge all these other holidays, why not us?’”

New China Chic

While that speaks to one side of the equation—the uphill battle to get people outside of China to embrace a Chinese garment—what about the other side? Why do Chinese people today show such tepid interest in reclaiming a garment that is theirs (or at least their mother’s?)

Tam also has some insight into this. Because China was closed off during the early Communist years, when global trade opened in 1978 the population didn’t want Chinese goods or designs. They hungered for anything western, turning them into the most fervent of luxury shoppers.

“At that time, everybody told me that you will never be successful,” said Tam. “Nobody, nobody will buy from you because Chinese don't like Asian brands. They only appreciate Western brands.”

While that mindset has loosened its grip over the years—younger Chinese consumers and designers both have gained confidence—a sense of national pride still needs to counterbalanced with avoiding chinoiserie caricature like Shanghai Tang.

Without a heavy lift of educating the customer, there’s a limited addressable market, Tam added. Newer Chinese designers “probably don’t think there’s enough money in making it,” she said.

If you look at the Labelhood x Harrods Lunar New Year capsule which features 15 Chinese designers—including Uma Wang, Yan Yan Knits, Xu Zhi—only Samuel Guiyang produces attire that is recognizably Chinese at a distance.

His entire line is predicated on that concept, not just for a few weeks during Lunar New Year. But as I’m based in New York, my gripe is there’s no way to buy any of it. It’s not listed on Harrods ecommerce because I’m sure they produced in pretty limited numbers. With luxury ecommerce in the state it is, it’s gotten harder to buy from emerging designers overall.

I can plan to make a few cheongsams strategically on future trips back to Asia but that too may not be on the table for much longer. Most of the tailors are well into their octogenarian years and are planning to retire soon. According to this AFP article, there’s only ten remaining in Hong Kong down from around 1,000 in the mid-sixties, making the craft “critically endangered”, according to the Hong Kong Cheongsam Association.

Which leads me to wonder, will the baton at that point pass to brands? I understand why international brands don’t necessarily feel up to the task of producing the garment but Chinese designers working with its codes haven’t reached a critical mass either. When I turn 60, what will be available to me then? I’m really not sure. But I do know that just putting on red clothing with an animal accent for the holiday seems like a cop out.

For now, I’ll settle for simply wishing everyone a very prosperous year of the snake and the shedding of yesteryear’s limitations. 祝大家蛇分美滿, 蛇蛇如意!

P.S. Am I missing any great LNY-friendly labels? If there are names I should check out, I would love to know.

Also On My Mind:

NYFW roundup: Marc Jacobs proved once again why he’s Marc Jacobs with some wonderfully weird inflated dolls. Calvin Klein also returned to the runway after a seven-year hiatus debuting its first female designer. Unfortunately, critics deemed it “not that sexy” and “dead on arrival”. On a happier note, hats off to Olivia Cheng of Dauphinette who won the CFDA/Genesis House AAPI award.

Kering’s slump continues. It reported Q4 earnings that dropped 12% yoy, while Gucci, its main brand fell double that by 24%. Just days prior, the brand announced it had axed its creative director Sabato de Sarno after just two years on the job, an admission its revival attempt had failed.

How is fashion criticism changing? Tim Blanks, Vanessa Friedman, and Rachel Tashjian discuss over at Cultured Magazine. Best takeaway? “There’s a difference between commentary and criticism.”—Tashjian.

Vogue wants you to believe that Hailey Bieber is bringing back the babushka headscarf. But I say it’s Keinemusik. Love em or hate em, &ME stans and Camilla Cabello will back me up on this.

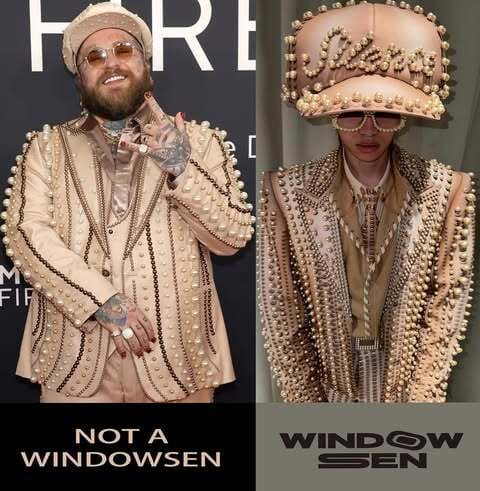

Nooo, Teddy Swims why would you do this? Young Chinese label Windowsen called out the singer for wearing a pretty blatant ripoff of his design at the Grammy’s, even showing the receipts where Swims’ team reached out asking for the look. Designer Sensen Lii declined because it was a one-off reserved for Chinese popstar, Silence Wang. Then Swims proceeded to work with Kay Jewelers to dupe the pearled fit.

I hate that Lii has gotten shafted by western celebrities more than once. Cardi B wore Windowsen to the MET Gala last year but forgot the brand name saying vaguely that it was an “Asian designer”. Keep in mind that these looks are created basically for free in exchange for exposure. Cardi did apologize and posted the brand name on social later but we can do way better than this. So for a lil primer on Lii’s fantastical otherworldly designs, check out my write up of his debut in 2021.

Trump’s 10% tariffs on all goods from China kicked in. De minimis sees its demise, closing a loophole that propelled Shein and Temu to their success. Shein stands to lose more than Temu. But of course, China has retaliated putting Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger’s China business on the line.

Trump also floated creating an American sovereign fund to take control of TikTok, which was thrown a lifeline but still has to find a buyer by April. There are signs that Beijing won’t agree to any sale though.

I wrote a feature for Rest of World about why western social apps can’t replicate the addictiveness of Chinese ones. Spoiler: It’s because the model in China has already moved to ecommerce, diversifying from advertising. Shout out to Ryan Broderick for this mic-drop quote: “Something western companies like Meta have not ever been able to crack, possibly because, ironically enough, they aren’t nearly as focused on directly selling you s***, and much more interested in selling you to advertisers.”

As someone who became a cool aunt fairly recently, I approve of this “時髦小姨“ trend.

Comments or questions? Drop me a note below. And if you know someone who would enjoy this newsletter or find it useful, go ahead and share it with them.

Reply